Competition law is a law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. In India, competition law is regulated through the Competition Act, 2002 with the objective “to prevent practices having an adverse effect on competition, to promote and sustain competition in markets, to protect the interests of consumers and to ensure freedom of trade carried on by other participants in markets, in India, and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”[1]

Competition law is a law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. In India, competition law is regulated through the Competition Act, 2002 with the objective “to prevent practices having an adverse effect on competition, to promote and sustain competition in markets, to protect the interests of consumers and to ensure freedom of trade carried on by other participants in markets, in India, and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”[1]

The provisions dealing with anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance, monopolistic and restrictive trade practices were effectuated on 20th May 2009. The Competition Act, 2002 (the Act), in concurrence with various other regulations makes a complete apparatus for competition in India. The Competition Commission of India (CCI), established under Section 7 of the Act, is the principal regulating body for Anti-Trust/Competitive behaviour across all sectors even though there are many other sectorial regulators that are in charge of maintaining healthy competition in their respective industries.

The order of the CCI can be appealed before the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) and its order is finally appealable before the Supreme Court of India (SC).

The regulation on cartels within the Competition Act, addresses the most important issue legal practitioners face to alleviate the fines that are levied on legal entities by the Tribunal on the basis of the reporting done by the anti-trust authorities. The cartel regulation covers important aspects of anti-competitive and unfair trade practices scrutinized by agencies such as industry-specific offences, the process and procedure of an investigation, investigative powers of the anti-trust authorities, interchange between jurisdictions, arbitration; criminal, civil and administrative sanctions, damages claims, leniency and amnesty regime, cartel enforcement action, right of appeal against civil liability, reform proposals, administrative settlement of cases (plea bargaining), cross – border issues among others.

In the cases of anti-competitive conduct, the CCI can impose a penalty that cannot be more than 10% of the average turnover of the contravening entity for the previous three financial years. In the cases of cartels, the CCI can impose a penalty of up to three times the profit of the contravening enterprise or 10 % of the turnover of the contravening enterprise, for each year of the continuance of the cartel, whichever is greater, and the directors and other employees of the contravening enterprise if found responsible, can also be held liable for a penalty under the Act.

As far as the pieces of evidence are concerned, for proving a cartel has happened, it has been held by the CCI that an economic crisis arising out of a cartel is of utmost importance to issue sanctions against it, mere agreement by itself cannot be the basis of a cartel prosecution. There are numerous cases that have shown that CCI not only relies on direct and indirect shreds of evidence but also economic analysis breakdown and investigation to prosecute a cartel. Anti-competitive agreements do not have any criminal liability in India, but on the contrary, criminal sanctions can be issued for non-compliance with the orders of the CCI or the NCLAT.

Competition jurisprudence is still in the developing stage in India. The legal fraternity including practitioners and the Commission rely a lot on the precedents set by the courts of the United States and the European Commission for directions. As of now, CCI has not given specific guidelines and regulations for cartels. CCI has been very operational in conducting raids and locating and curating existing cartels for trials, but as far as Competition Jurisprudence is concerned, we are yet to formulate it in many aspects; because most decisions given by NCLAT are not contrary to the provisions of the Competition Act, and neither do they expand the legal requirements for quasi-judicial actions. The Supreme Court of India vide its landmark judgement on cartels, allowed the appeals by the 44 LPG Cylinder manufacturers and dismissed the finding of bid-rigging in supply of 14.2 kg domestic LPG cylinders to the Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. (IOCL), quashing the Order of the erstwhile Competition Appellate Tribunal (COMPAT) which had earlier upheld the finding of the CCI, which had also imposed penalties on each party @ 10% of their average relevant turnover.[2]

The apex court has been relying upon precedents and guidelines on price rigging from various foreign jurisdictions has time and again asserted the need to evaluate the market scenario before arriving at any conclusions of establishing the fact that a cartel has happened. This judgment upheld that there was insufficient evidence to establish an agreement between them regarding collusive bidding, and has set a trend likely to bring a change in the manner of evaluation of evidence on cartels by the antitrust regulator in future.[3]

The Competition Act also does not give provisions for “the private enforcement of rights”. NCLAT is yet to pass an order addressing a claim of damages and private parties have to file Compensation claims, before the NCLAT. While there are no judgements to date on any compensation claims by the NCLAT, presently, NCLAT is considering a number of compensation claims like a pending compensation application of Coal India against CCI’s decision in 2014. The damages jurisprudence on matters of cartels is yet to formulate in India.

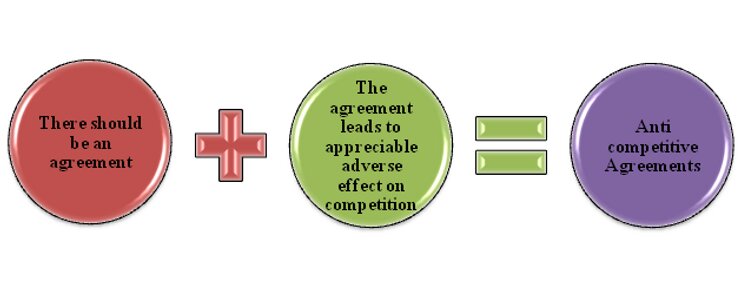

A recuperative measure can be taken by an aggrieved party if the contravention of the substantive provisions of the Competition Act, has caused any loss, it can approach NCLAT for an award of ‘restitutive compensation’ as given under section 53 A of the Act. The foundation of formulating jurisprudence is not to ignore the principle of natural justice, and having said that it is pertinent to note that evidence of anti-trust effects is extremely important to establish a contravention, including the cases of entrenched cartels. The major setbacks are imposing admonitory and arbitrary levels of fines, inadequate evidence, misuse of progressive provisions such as leniency schemes, dawn raids, conflicting policies of the government and regulations governing cartels. To sustain the findings of the competition authorities, analysis of the definition of “agreement” under the Act is of utmost importance. The Indian Competition law quite broadly defines the definition of agreement that includes any arrangement or understanding or action intended to be legally enforceable.

In the absence of the above mentioned unaddressed aspects that cause setbacks to the entities, CCI has been hasty to presume the existence of an agreement that has adverse effects on the competition, where such arguments will questionably take centre stage during the adjudication. CCI’s quick disposals of cases are likely to lead to inadvertent consequences and cause accidental damage. Therefore, India’s Competitive Jurisprudence is in the need of developing a more economic approach.

In the end, I would conclude by quoting Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (Associate Justice of Supreme Court of United States):

“Liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt.”

Subscribe to The Fin Lit Project to learn more about such aspects of Finance and we will make finance simple and accessible for you!

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[3] Rajasthan Cylinders and Containers Ltd v Union of India & Anr Civil Appeal 3546 of 2014, Order dated 1 October 2018.